In Formula 1, you need to have a few elements if you wish to be successful. You need a certain degree of natural talent. You need to be willing to work hard. You need to understand circuits, and you need a certain measure of aggression. You also need to understand the car; it’s characteristics on any given track, how it responds to you, how you respond to it, and so forth. Being able to adapt the car to suit your style is crucial to victory. Finally, a good understanding of how to look after tyres, and manage fuel, never goes amiss.

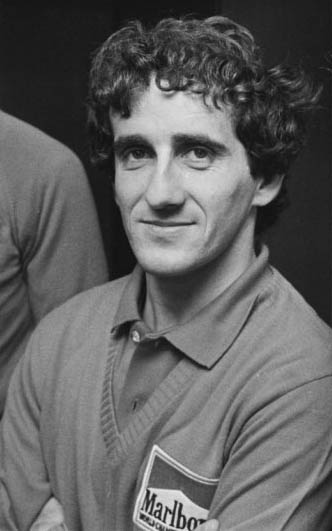

In respect of mastering car setup and managing the consumables, it can be argued no one nailed these aspects better than Alain Prost. Indeed, such was his ability to lock in a car setup, and his talent for managing fuel and tyres, that he earned the nickname of The Professor in the F1 paddock. He combined this with a healthy dose of raw skill for good measure, and these attributes carried him to four world championships, and 51 race wins. However, what defines Prost more so than anything else is his part in an epic rivalry that transcended Formula 1. More on that later.

Learning the Ropes

Years before he would find himself tangling with the likes of Nelson Piquet, Nigel Mansell and Ayrton Senna, Prost, who discovered karting at the age of 14, was crushing all opposition in the feeder series’. He won the French senior karting championship in 1975, and the following year made the leap to single-seater cars. He immediately won the French Formula Renault, and did so by winning all but one race. In 1977 he won the Formula Renault European Championship, and in 1978 won both the French Formula Three title, whilst also competing in the European Formula Three Championship. In 1979 he once again competed in both series, and won them both as well. This pattern of serial winning was enough to gain the attention of Formula 1 teams, and McLaren were the ones to nab his signature.

Making the Jump

Prost gained an early distinction, by scoring points on his debut, something that only happened three times between 1973 and 1993. He raced quite well, considering his inexperience, but his first year in F1 was also marked by several accidents, which included breaking his wrist at the South African Grand Prix. He grew unhappy at voices inside the team, believing he was being unfairly blamed for some of those accidents, and he was displeased with the frequency of mechanical failures as well. He left McLaren after just one year, and signed for Renault instead. Here he immediately clashed with fellow Frenchman Rene Arnoux, who was said to have been aggravated by Prost’s pace. It was clear who the quicker driver was, and Prost would claim not only his debut win, but three in total in 1981, defeating Arnoux in the standings. In 1982 he won the first two rounds of the season, but suffered from reliability issues that greatly scuppered his hopes of greater things.

The tension with Arnoux, who was a firm favourite in France, and gripes about the Renault team, were creating other problems. Prost’s relationship with the French media was poor. In Prost’s own words, “When I went to Renault the journalists wrote good things about me, but by 1982 I had become the bad guy. I think, to be honest, I had made the mistake of winning! The French don’t really like winners.”

Arnoux left Renault at the end of 1982, and Prost remained, partnered by American Eddie Cheever. Here, Prost went agonisingly close to the championship, winning four races, but Nelson Piquet of Brabham clinched the title at the final race, owing to a turbo failure for Prost. It was a bitterly disappointing moment, and Prost would go on to criticise the team, blaming them for producing an uncompetitive car. Consequently, Renault fired Prost, and he resigned for McLaren. He had to leave France when Renault factory workers burned one of his cars.

The Narrowest Margins

Formula 1 sometimes conjures up moments that defy all expectations. Upon returning to McLaren, Prost was partnered with the legendary Niki Lauda. Lauda, a two-time world champion with his own remarkable story, and Prost would dominate the 1984 season, winning 12 of 16 races. Their title battle was largely a private duel, with the talent of Prost versus the experience and guile of Lauda. Though Prost took seven wins to Lauda’s five, one of those victories – at Monaco – saw half-points awarded when the race was ended early, and this was at Prost’s urging.

The race itself was extremely wet, to a degree rarely seen at Monaco, before or since. With numerous cars sliding into the barriers, Prost held his own to lead, but with Senna bearing down on him (despite an inferior car, Senna was lapping several seconds quicker), on lap 26 Prost signalled to race officials to end the race early. On lap 29, Prost pulled over and stopped, and Senna went by him into the lead, but with rules stating that the race order would be determined from the position on the previous lap, Prost was handed the win. Nonetheless, the difference between him and Lauda at the end of the season was half a point in Lauda’s favour, the smallest margin of victory in F1 history.

Breaking the Ceiling

By now, the general consensus of the paddock was that Prost was the most talented, quickest driver on the grid. He had gone close, but would he now finally achieve his ambition? In a season that a host of different winners (and debut wins for Senna and Mansell), 1985 would see Prost ultimately look quite comfortable on his course to his first F1 crown. In particular, a strong middle part of the season (which featured three of his five wins, and seven consecutive podium finishes) saw off the threat of the Ferrari of Michele Alboreto. He won the title with fourth place at the European Grand Prix at Brands Hatch, and perhaps not surprisingly, this felt like vindication after going so close more than once. The ceiling had been well and truly broken, and Prost, regarded by many of his peers as the best on the grid, was world champion.

Repeating the Feat

1986 might have been a private fight between the Williams duo of Mansell and Piquet, but Prost kept himself in the mix via his good management of tyres and fuel, and his ability to tune the car to be as quick as possible. He finished on the podium 11 times in 16 races, in fact he finished on the podium in all but two of the races he completed. Nonetheless, the infamous tyre blow-out Mansell suffered at the final round handed Prost the title. Still, Prost had put himself in the pocket, so to speak, to seize the opportunity had it arisen, for which he can’t be faulted, and his consistency was remarkable.

Even so, he was powerless to make it a hat-trick of world championships in 1987, with Williams pushing the development of their car to new heights. Though he would win two of the first three races, even Prost’s vaunted skills could not overcome the gap in car performance. The performance would swing radically in his favour for 1988, with the arrival of Honda engines to McLaren, but those engines came with a cost…

The Biggest Challenge in the Best Car

The 1988 season was the last of the turbocharged era, until 2014’s new rules. The MP4/4 was McLaren’s entry, and the car itself has gone down as one of the most legendary to ever grace a race track. The design was sturdy and rugged, and the Honda engine was supremely powerful. Honda had switched from supplying Williams to McLaren due to the influence of Ayrton Senna, who had established a good relationship with the company during his time racing for Lotus. Signing Senna was therefore a major boost for McLaren, in more ways than one. Prost himself initially approved of the arrival of the talented Brazilian, who had firmly established himself as a skillful racer.

What Prost had perhaps not reckoned with was just how ambitious his new teammate would be. Senna had set his sights on becoming the very best, and he relished the challenge of the two-time world champion. The situation was aided – or not, depending on your perspective – by McLaren being by far and away the dominant team of 1988. No one was anywhere near them, so the title fight became a private duel between Prost and Senna. The two would share on-track duels and tactical battles for success, with Prost at one stage said to be rattled by Senna’s copying of his setups. At the Belgian Grand Prix, Prost made a last-minute change to his car, hoping to out-fox Senna, but instead Prost outdid himself.

The titanic fight for the 1988 title ended in Japan, where Senna came back from stalling at the start to win, whilst Prost, between his dislike of racing in the wet, and gearbox problems, could only maintain second place. Senna’s victory meant he was world champion, and Prost, whilst not happy with F1’s scoring system, accepted this.

There had been flickers of tension between Prost and Senna in 1988, as was to be expected when two tremendous talents duked it out for glory. In was in 1989 that this rivalry truly ignited. Between claims of reneging on pre-race agreements, and accusations of favouritism, Prost’s relationship with Senna and with McLaren deteriorated. Prost believed the team – and engine supplier Honda – were giving Senna preferential treatment. His row with the team, and his teammate, grew steadily public, and it fascinated the media. Prost decided after the San Marino Grand Prix – which Senna won after passing Prost at a restart – he would not speak to Senna anymore. During the season, he also announced he would be joining Ferrari in 1990.

The rivalry was pushing both men to greater heights of racing skill, but also acrimony. In a season where Prost enjoyed better results, he arrived at Suzuka, Japan, knowing he could seal the title at the penultimate race, whilst Senna had to win both remaining rounds to be in with a chance. Prost led much of the race from Senna, but Senna doggedly hunted down the Frenchman, and on lap 47 attempted to pass him at the final chicane, darting down the inside of the corner. Prost either did not see Senna, or chose to take the racing line as the lead driver, and the two collided. Prost immediately retired, believing the race and title fight to be over. Senna was able to bump-start his car, resuming his race, and he would eventually win, but was disqualified due to cutting the chicane.

Prost was world champion for a third time, albeit with question marks over the circumstances. Senna was highly aggrieved with F1 bosses, and what he perceived as favouritism toward Prost by FISA boss Jean-Marie Balestre (a fellow Frenchman). This would prove to have enormous consequences, nearly a year later.

A Master of Manipulation

Ferrari had been considerably inconsistent for many years, so Prost had taken a risk, trading a good car – albeit in a fraught environment – for a team that had only occasionally produced a car capable of winning races (and certainly not one able to challenge for championships). He partnered Nigel Mansell, and virtually from the start of their time together, it was clear that Prost was quicker, but also that he enjoyed the lion’s share of reliabilty.

On a personal note, this is where this meerkat takes issue with Prost. He was quick, as quick as anyone, but he also operated within a somewhat hypocritical region. He had been aggravated by his belief that McLaren were favouring Senna over him, yet when Prost joined Ferrari, he immediately took steps to ensure the team favoured him. One of the most famous examples of this was at the French Grand Prix. In qualifying Mansell proved faster than Prost, so Prost had their cars swapped around, for the next race, the British Grand Prix, without informing Mansell. This kind of underhanded move has, for me at least, blighted Prost.

Whilst Prost continued to duel with Senna for the title (Ferrari had produced one competitive car, and one unreliable one), he found their roles somewhat reversed from 1989. The pair arrived at Suzuka with Senna on the brink of his second title; Prost qualified second, behind his foe, and here, more controversy, perhaps the biggest incident between the pair, would erupt. Senna remained angry over the events of 1989, and his mood was not enhanced by the decision to have the polesitter start from the dirtier, less grippy side of the track. Senna felt this handed Prost an unfair advantage, and resolved to not allow his rival by, under any circumstances. Sure enough, at the start of the race, Prost got a better start, and had the inside line into the fast first corner, but Senna abruptly closed the door, the two collided, and both went out. Senna was world champion, and Prost was furious.

In fact, Prost was so angry that he considered retiring there and then. He called Senna ‘a man without value’, and perhaps he had a point. Senna had chosen – though he denied it at the time, and confessed to it a year later – to deliberately ram Prost.

The fallout was intense. The pinnacle of open-wheel racing had seen its two greatest stars embroiled in three years of increasing hostility, and for two years running, the world championship had been decided by hugely controversial collisions. Where would the story go next?

The immediate answer was nowhere. In 1991 Ferrari failed to deliver a competitive car, and Prost struggled. He grew increasingly annoyed, to the stage where he publicly denounced the car at the penultimate race, calling it a truck. Ferrari took a dim view of one of their drivers, even one as great as Prost, offering such a public criticism, and sacked him with one race still to go. By then, it was too late for him to find a seat for 1992, so Prost sat out the season.

Manoeuvres Behind the Scenes

Whilst Prost was not racing in 1992, he wanted to be, and he wanted a good car for 1993. In 1992 Williams clearly emerged as the best team, with developments to their car giving Mansell an unassailable advantage over his competitors, and Prost wanted that opportunity. He entered into negotiations with Williams, but there were complications. Mansell was said to be unsettled by the prospect, citing Prost’s manipulative efforts in 1990 at Ferrari. Further difficulties arose with Senna desiring a seat at Williams, and the Brazilian even offered to drive for free. Prost had no desire to partner Senna, and was able to not only get a contract for 1993, he was able to insert a clause forbidding Senna from joining the team! Needless to say, Senna was not impressed, and called out Prost for his cowardice.

Senna’s words did not dissuade Prost from his path. For 1993, Prost had the best car by some margin, as well as a relatively inexperienced teammate in the form of Damon Hill. His year out from the sport had not dampened his enthusiasm nor his skills, and despite a surprising early challenge from Senna (who was stuck with an inferior McLaren), Prost secured his fourth and final world championship with two races to spare. At the final round of the 1993 season, which Senna won, the Brazilian embraced his old foe on the podium, signalling the end of their epic rivalry.

This was not the end of Prost’s involvement in Formula 1. He remained in contact with Senna, of all people, and they discussed the ill-fated 1994 Williams, the FW16. Senna was eager to hear Prost’s thoughts on this unstable F1 car, and such was their renewed respect for one another that in the wake of Senna’s death, Prost was a pallbearer at the funeral. A few years later, Prost turned his hand to managing an F1 team, buying the Ligier team in February 1997, and renaming it Prost. Across five seasons, results proved modest at best, with a total of three podiums (two second places, and one third-placed finish) providing the highlights.

It would prove best to recall Alain Prost’s record as a racing driver. along with four world championships, he won 51 races, had 33 pole positions, and has 41 fastest laps to his name. Whilst I retain some personal misgivings about his sly, almost political approach to certain situations, it would be a mistake to ignore his on-track accomplishments.

‘Kat Comments